Students learn the best when they want to learn. Indeed, it is essentially a truism that motivated students will work harder and learn more than their less motivated counterparts. Crucially, the factors undlying people’s motivations matter too (Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier, & Ryan, 2011; Ryan & Deci, 2000a). On the one hand, students may be motivated to do well in the classroom so as to avoid punishment from their parents or to maintain a particular GPA, reflecting a more controlled motivation. On the other hand, students may be motivated to do well because they deeply believe in the importance of the material they are learning or else because they find the material to be fascinating, reflecting a more autonomous motivation. A large literature in psychology supports the notion that autonomous motivation is far more beneficial for achievement and well-being than is controlled motivation (e.g., Kusurkar, Ten Cate, Vos, Westers, & Croiset, 2013; Núñez, Fernández, León, & Grijalvo, 2015). The aim of the present work is to explore within a naturalistic classroom setting what predicts students’ endorsement of autonomous versus controlled motivations to perform well in the class.

Autonomous verus Controlled Motivation

The distinction between autonomous and controlled motivation has its roots in Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Autonomous motivation originates within the self and comprises primarily of two types. First, autonomous motivation can involve pursuit of a task or goal for reasons of interest or enjoyment, as when people play games for fun or read books to satisfy their curiosity. Second, autonomous motivation can involve pursuit of a task or goal due to its congruence with one’s internalized values and beliefs. People who engage in political protests via risky behaviors (e.g., going on a hunger strike), for example, are often motivated by deeply held moral convictions. Controlled motivation, in contrast, originates outside of the self and also comprises primarily of two types. First, controlled motivation can involve pursuing a task or goal due to some internalized social pressure, as when a person feels obligated to maintain a nice yard and does to to avoid the guilt or shame that would result otherwise. Second, controlled motivation can involve pursuing a task or goal due to outside pressure, coercion, or seduction, as when a person engages in some behavior to avoid punishment or to attain some reward.

Whether people are motivated by more autonomous versus controlled reasons has profound implications. People are more likely to succeed when pursuing a goal for autonomous reasons than for controlled ones (e.g., Kusurkar et al., 2013). Moreover, when people are pursuing autonomous goals rather than controlled ones, they typically work more creatively and are better problem solvers (Black & Deci, 2000; Liu, Chen, & Yao, 2011). How goal pursuit is experienced also varies as a function of its underlying motives. When pursuing autonomously motivated (vs. controlled) goals, people are more invigorated, less fatigued, and happier (Muraven, Gagné, & Rosman, 2008; Nix, Ryan, Manly, & Deci, 1999). Moreover, people whose daily pursuits tend to involve more autonomously motivated goals than controlled ones report greater mental well-being and physical health than do people whose pursuits are more controlled (Ryan & Deci, 2000b). To pursue goals for autonomous reasons thus appears to be linked to a wide range of positive outcomes.

Fostering Autonomy. Ample research has examined the various ways in which people can foster autonomy in others (e.g., Núñez & León, 2015). There are three major ways that people can do this (e.g., Su & Reeve, 2011). First, people can foster autonomy by making a task more enjoyable. If a task can be made more fun or more interesting, then people will be more autonomously motivated to do it. Second, people can foster autonomy by making a task more valuable. If people can be shown that a task is congruent with their deeply held values and beliefs, then people will be more autonomously motivated to do it. Third, people can foster the degree to which one can exercise their personal preferences in how they pursue the task. If people are able to make choices for how they pursue a task, it will feel more autonomous.

In the present project, I tracked students’ experiences and motivations in a particular course throughout the semester to test whether certain classroom experiences are predictive of students’ autonomous motivations over time. Although prior research has tested predictors of students’ autonomous motivation (e.g., Núñez & Leon, 2015), that work has focused mostly on practices and perceptions of teachers rather than of the courses as a whole (e.g., Jang, Kim, & Reeve, 2012); has focused only on singular aspects of a course (e.g., focusing only on perceived choice; Patall, Cooper, & Wynn, 2010); or has employed cross-sectional study designs examining a single time point rather than longitudinal designs tracking motivation over time (e.g., Roth, Assor, Kanat-Maymon, & Kaplan, 2007). The present work, in contrast, is focused on students’ perceptions of the course as a whole, measures simultaneously multiple aspects of the course to test which factors are predictive of autonomous motivation over and above the others, and employs a longitudinal design that can provide stronger support for a causal influence of classroom perceptions on autonomous motivation via cross-lagged analyses. This project thus satisfies recent calls for more longitudinal field studies assessing multiple predictors of classroom motivation over time (Guay et al., 2008; Núñez & Leon, 2015).

I tracked psychology majors’ and minors’ autonomous motivations in a research methods and statistics class. I also tracked students’ classroom experiences, looking specifically at experiences that had the potential to be linked to felt autonomy. My aims in this project were to gain a better understanding of how students’ motivations changed in my research methods class over time, the experiences in that class that were associated with motivation change, and perhaps the experiences that were associated with autonomous motivation change in general. An additional aim was to carry out this project using R with the help of the Faculty Learning Community on SOTL and R, thereby creating in myself a new skillset and knowledge base to apply on future projects.

Measuring Autonomous Motivation and Classroom Experiences

I measured autonomous motivation with a standard measure used in the literature (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). The measure asks people to what extent they are pursuing a goal for some external purpose (e.g., to gain a reward or avoid some punishment), to avoid negative emotions associated with failing to meet obligations, due to internalized values and beliefs, or due to intrinsic interest and enjoyment. To the degree that people are motivated by the latter two reasons, they are more autonomously motivated.

I also measured various classroom experiences that I suspected might be linked to the degree to which people’s motivations were more autonomous versus controlled. First, I measured students’ perceived difficulty of the class and to what extent students thought they could do well in the course (i.e. their self-efficacy). As students begin to struggle in a class, they may become more focused on potential negative outcomes (e.g, of disappointing their parents or failing to meet obligations), and this may be associated with becoming more controlled in their motivation. Second, I measured students’ perceived involvement in the course. That is, I measured to what extent students felt like active participants in the class. To the extent that students felt like they were contributing to the class – bringing their own ideas, preferences, and decisions to the classroom experience – they may have felt more autonomously motivated.

Third, I measured the degree to which students reported having a big picture appreciation for the course content. This is the degree to which students reported seeing the value and importance of classroom content and exercises. If students are able to see the value in what they do in class, then they may be more autonomously motivated.

Last, I also measured students’ classroom rapport, which is the degree to which students’ reported a sense of social belongingness in the class. If students feel like they belong in a class, then this may make them enjoy and value the class more, and this in turn may be linked to being more autonomously motivated to do well in the class. I measured the above classroom experiences not only because I had reason to suspect they could be linked to felt autonomy but also because I strive actively to increase these experiences in the classroom. Much of my communication in the classroom is aimed at encouraging students’ self-efficacy. I also often reach out to individual students who are struggling in the class with the goal of helping them to learn the material as well as encouraging them to feel as though they can succeed in the course. I also include many activities in the classroom and in lab sections to encourage perceived involvement. I try to make as many aspects of the course as possible (e.g., assignments, exercises, papers, in-class examples) reflect students’ own preferences and interests. In addition, I try to encourage a big picture appreciation of the course content by regularly returning to the overarching themes in the course and providing ongoing summaries that link together all we’ve done in the class. Finally, I foster classroom rapport via activities done in small groups and as lab sections.

Thus, in the present project, I measured students’ motivations and the five classroom experiences described above: perceived difficulty, self-efficacy, perceived involvement, big picture appreciation, and classroom rapport. I measured each of these during the first week of class and every other week thereafter until the end of the semester.

Classroom Selection

I decided to carry out this project in my research methods and statistics class because it is a challenging class in which students typically struggle and where I suspect students tend not to be as autonomously motivated as they are in other psychology classes. As described above, it is also a class in which I expend a lot of effort encouraging autonomy in the classroom, with the aim of improving student engagement and performance. The present project will allow me to test to what extent students do tend to adopt more controlled rather than autonomous motivations in the clasroom and what sorts of classroom experiences predict students’ motivations. This is a uniqiue class, and it is not clear whether the patterns observed within it will generalize to other classes. However, if I do ultimately measure similar experiences and motivations in other classes, then this project could serve as an initial test of the more general patterns that capture student motivations in the classroom in higher education.

Use of R

I carried out all aspects of this project using R. This includes importing my data via R, wrangling my data in R, conducting all data analyses and visualizations in R, and producing the present write-up in R. I had very little experience with R prior to this project. Therefore, the current project served as a space in which to practice and learn doing all aspects of a research project in R. The hope is that this project helped me to learn enough about R so that I can continue to use R in future teaching and research projects, allowing for more flexible and reproducible work in both arenas.

Participants

Participants were 68 students enrolled in a class on research methods and statistics in psychology during the spring 2019 semester. All students were psychology majors or minors, ranging from sophomores to seniors.

Materials

The project involved just a single questionnaire with several items. In the questionnaire, students first answered five questions about their experiences in the course. They indicate how challenging they thought the course was overall (perceived difficulty), how confident they were that they could do well in the couse (self-efficacy), how much they currently felt like an active participant in the course (perceived involvement), to what extent class meetings were helping them to see the big picture relevance of what they were learning (big picture appreciation), and to what extent they felt like they had a good rapport with others in the class (classroom rapport). Each of these items was answered on a 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) scale.

Second, students answered four questions aimed at measuring their motivation in terms of how autonomous versus controlled it was. Specifically, students were asked to indicate why doing well in the course was important to them. They were presented with four reasons: “Because somebody else wants me to, or because the situation seems to compel it,” “Because I would feel ashamed, anxious, or guilty if I didn’t,” “Because I really believe that it’s important to,” and “Because of the enjoyment or stimulation that the course bring.” Participants rated each item on a 1 (Not at all because of this reason) to 7 (Completely because of this reason) scale.

Procedure

All students completed the questionnaire during the first week of class and then again each other week until the end of the semester. Students received a link to the questionnaire via e-mail on the Thursday of each week and were asked to complete it by the end of Saturday. The questionnaire was hosted on the Qualtrics website. Students were invited to complete the survey at eight different time points.

I conducted all data analyses in R, using the ggplot2 and lme4 packages for data visualization and mixed effects model analyses, respectively. For each student at each time point, I calculated an autonomous motivation score. I did this by summing the third and fourth items in the autonomous motivation measure and subtracting from that the sum of the first and second items.

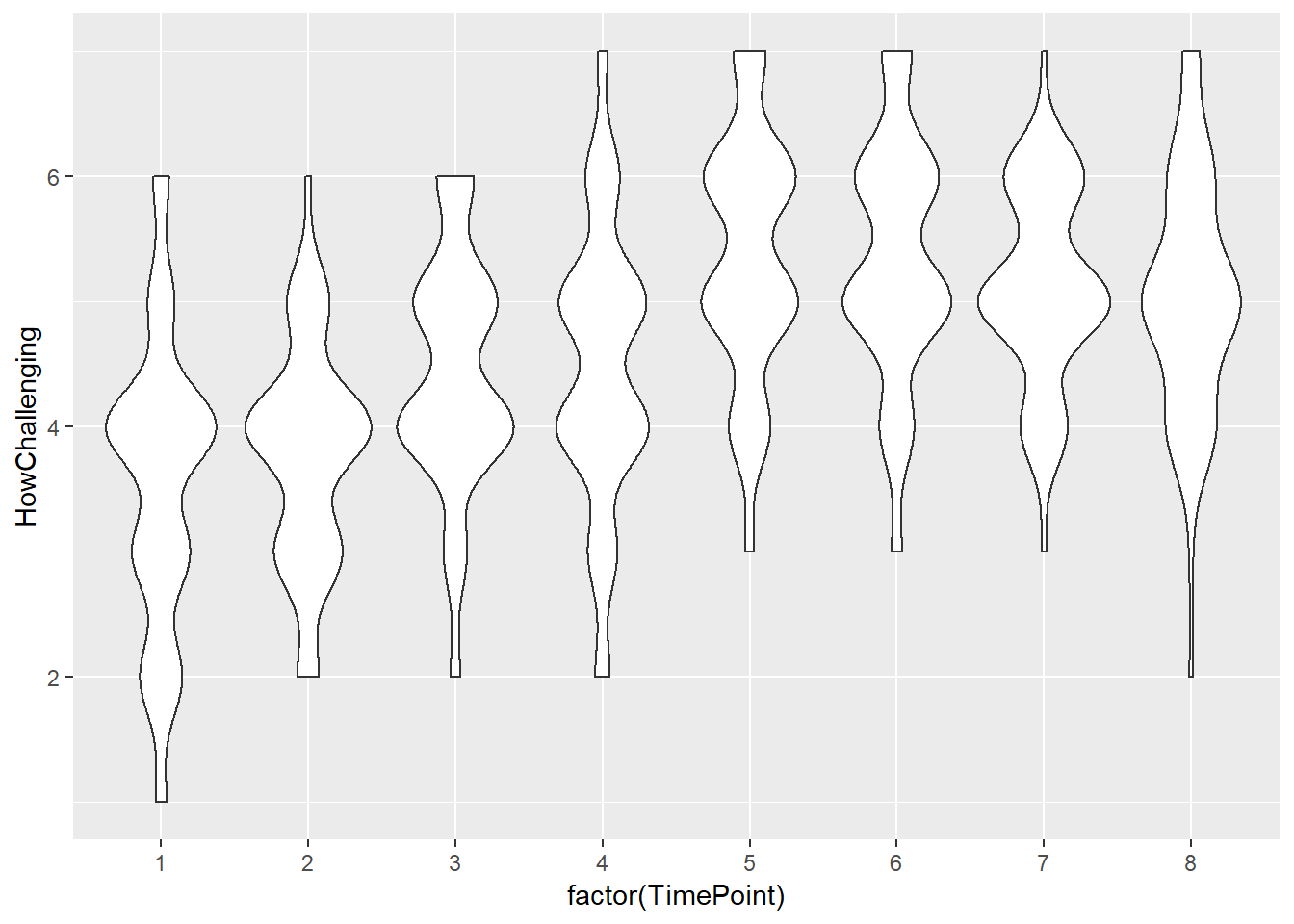

I first analyzed changes in students’ class perceptions and autonomous motivations over time. I did this using a series of within-subjects ANOVAs with time point as the within-subjects factor. Results revealed that perceived difficulty varied significantly across time points, F(1, 445) = 44.57, p < .001. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Perceived difficulty over time

Note. The above violin plot shows the distributions of students’ perceived difficulty ratings across all time points.

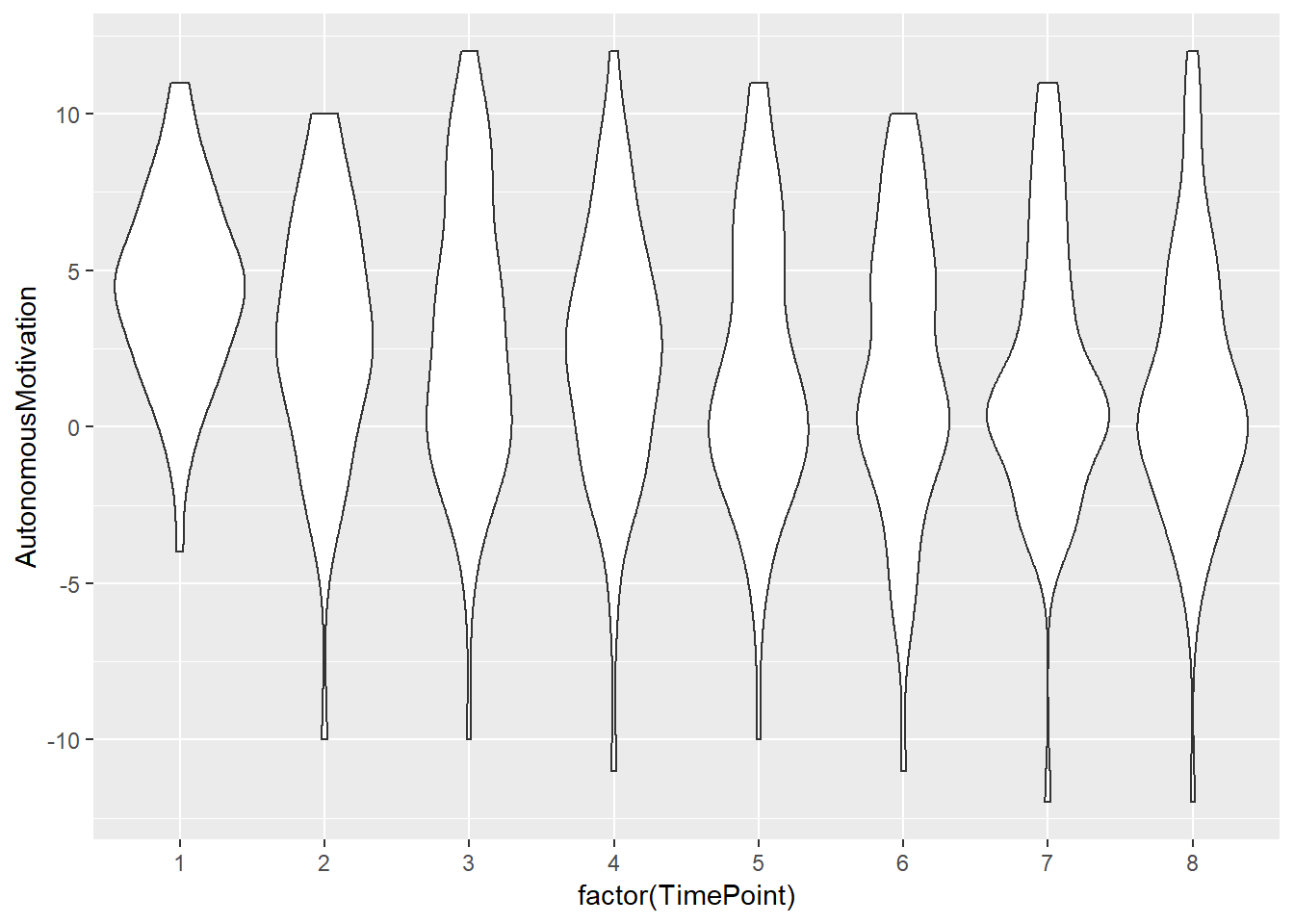

None of the other classroom perceptions (self-efficacy, perceived involvement, big picture appreciation, and good rapport) varied significantly across time, all |Fs| < 3.74, ps > .053. Autonomous motivation, however, did also vary significantly across time, F(1, 446) = 8.22, p = .004. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Note. The above violin plot shows the distributions of students’ autonomous motivation scores across all time points.

I next analyzed whether classroom perceptions were predictive of students’ autonomous motivation. I specifically wanted to test whether changes in students’ perceptions of the class were predictive of their current autonomous motivation. Thus, for each time point, I created change scores for each measure of interest (i.e. autonomous motivation scores and the five classroom perceptions). I computed these change scores by taking the students’ score at a particular time point and subtracting the student’s score for that variable from the most recent time point. Thus, change scores captured to what extent students’ classroom perceptions and experiences changed over the previous two weeks, with positive scores representing recent increases in that particular perception or experience.

To test whether changes in classroom perceptions predicted current autonomous motivation, I conducted a mixed effects model predicting autonomous motivation at the present time point; student and time point were random factors; and changes scores for the five classroom perceptions (self-effiacy, perceived involvement, big picture appreciation, and good rapport) as well as autonomous motivation at the previous time point served as fixed factors. The results revealed that change in perceived difficulty was significantly, uniquely linked to autonomous motivation, b = -0.21, SE = 0.11, t(296.62) = -2.00, p = .047. Thus, recent increases in perceived class difficulty tended to correspond with low levels of autonomous motivation. Change in self-efficacy was also significantly, uniquely linked to autonomous motivation, b = 0.22, SE = 0.11, t(330.45) = 2.04, p = .042, such that recent increases in self-efficacy tended to correspond with high levels of autonomous motivation. Change in perceived involvement was not significantly, uniquely linked to autonomous motivation, b = 0.18, SE = 0.11, t(329.72) = 1.58, p = .115. However, change in big picture appreciation was significantly, uniquely linked to autonomous motivation, b = 0.23, SE = 0.11, t(329.11) = 2.13, p = .034, such that recent increases in big picture appreciation tended to correspond with high levels of autonomous motivation. Finally, change in classroom rapport was significantly, uniquely linked to autonomous motivation, b = 0.31, SE = .12, t(327.01) = 2.52, p = .012, whereby recent increases in rapport tended to correspond with high levels of autonomous motivation. Autonomous motivation at the last time point was also significantly, uniquely linked to autonomous motivation in the present, b = 0.93, SE = 0.03, t(330.68) = 34.67, p < .001.

Exploratory analysis. As an exploratory analysis, I also tested whether changes in autonomous motivation were predictive of later classroom perceptions. For each of the five classroom percpetions, I conducted a mixed effects model predicting the classroom perception of interest; I used as random factors both student and time point; and, as fixed factors, I included the change in autonomous motivation since the most recent time point and previous scores (i.e. from the most recent time point) on the classroom perception of interest. Results revealed that changes in autonomous motivation were significantly predictive of self-efficacy, perceived involvement, big picture appreciation, and classroom rapport, ts > 4.20, ps < .001. Changes in autonomous motivation were not predictive, however, of perceived difficulty, b = -0.03, SE = 0.02, t(254.12) = -1.41, p = .160. Thus, recent increases in autonomous motivation tended to correspond with high levels of self-efficacy, big picture appreciation, and classroom rapport; it was not, however, linked to preceived class difficulty.

Some students are autonomously motivated to do well in a course, meaning they’re driven more so by a belief that the course is important and by instrinsic enjoyment of the course than by outside pressures to do well in the course. When students are so motivated, they tend to perform better in the course and to experience greater well-being while taking it (e.g, Guay, Ratelle, & Chanal, 2008). In the present work, I examined students’ experiences and motivations in a course where autonomous motivation varied significantly throughout the semeseter. The results revealed that a number of classroom perceptions predicted subsequent levels of autonomous motivation. As students perceived the course to become more difficult, their autonomous motivation decreased. However, as students’ perception that they could do well in the course increased, as their appreciation for the big picture relevance of the course increased, and as their rapport with others in the class increased, so did their autonomous motivation.

The above relationships were all unique from each other. That is, the links between perceived difficulty, self-efficacy, big picture appreciation, and classroom rapport with autonomy were all independent of one another. Thus, I found evidence that a number of classroom perceptions in parallel are predictive of shifts in autonomous motivation over time. In contrast, I did not find evidence that changes in perceived involvement in the course were predictive of levels of autonomous motivation.

These results are largely supportive of prior work on Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Prior SDT-related work argues that people are going to be more autonomously motivated toward a goal when they feel only moderately (not overly) challenged by it (Deci & Ryan, 1985); that valuing the importance and relevance of a goal is going to increase autonomous motivation toward it (Assor, Kaplan, & Roth, 2002); and that feelings of social connectedness in a classroom promotes autonomously motivated learning (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). The present work contributes to these ideas supporting evidence that these processes contribute to autonomous motivation over time in the classroom setting.

Prior work has also argued that students’ perception of being actively involved in a course (i.e. having choices within it) are predictive of their autonomous motivations (Patall et al., 2010). In the present wor, however, we did not find support for this link. The degree to which participants perceived themselves as becoming increasingly involved in the class over time did not predict high levels of autonomous motivation. One possibility is that perceived involvement is simply not independently predictive of autonomous motivation over and above the other factors that I measured in the present study. Prior work has tended to focus exclusively on choice while not considering these other influences (e.g., Patall et al., 2010). Another possibility is that perceived involvement and autonomy are indeed linked but that it is actually autonomy that promotes involvement rather than the reverse. Indeed, our data revealed that increases in autonomy over time did predict high levels of perceived involvement. It is therefore possible that prior work linking choice to autonomy via cross-sectional designs has found such a link (e.g., Patall et al., 2010) due to autonomously motivated students being more likely to exert themselves within the classroom. Yet another possible reason for the disconnect between the present findings and prior work may be due to ambiguity in the present measure, which asked participants to report on their level of participation in the class and did not necessarily emphasize making personal choices.

Exploratory analyses also revealed that recent increases in autonomous motivation were predictive of subsequent classroom perceptions. Specifically, when autonomous motivation increased, later levels of of self-efficacy, big picture appreciation, perceived involvement, and classroom rapport tended to be high. Thus, it appears not only that changes in classroom perceptions predict later autonomous motivation, but that changes in autonomous motivation predict later classroom perceptions and experiences. The relationship between autonomous motivation and various types of course engagement may therefore be bi-directional. By fostering certain classroom experiences, teachers may promote autonomous motivation in their students, and this increased autonomy may then make students more likely to have more engaging classroom experiences.

The present work has a number of limitations. First, these data were collected within a single class and so it is not clear whether the results will generalize to other students or to classes with differing content or teachers. Second, the data are all correlational and so it is not possible to make strong causal claims. Nevertheless, the longitudinal design offers far better support for causal links than typical cross-sectional designs do. Still future work should test the present research questions both in other classes and using experimental designs.

Conclusion. Students who are autonomously motivated are more engaged, higher performing, and happier than are other students. It is thus hugely beneficial to teach in a manner that encourages autonomy in one’s students. In the present work, I found that when students experienced increases in their perceived ability to do well in the course, their appreciation of the big picture relevance of the course material, and their social connectedness to others in the class, their autonomous motivation tended subsequently to be high. It appears that by fostering these perceptions within the classroom, teachers can foster autonomy and therefore success in their students.

Assor, A., Kaplan, H., & Roth, G. (2002). Choice is good, but relevance is excellent: Autonomy‐enhancing and suppressing teacher behaviours predicting students’ engagement in schoolwork. British journal of educational psychology, 72(2), 261-278.

Black, A. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). The effects of instructors’ autonomy support and students’ autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: A self‐determination theory perspective. Science education, 84(6), 740-756.

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational psychologist, 26(3-4), 325-346.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Guay, F., Ratelle, C., & Chanal, J. (2008). Optimal learning in optimal contexts: The role of self-determination in education. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 233-240.

Jang, H., Kim, E. J., & Reeve, J. (2012). Longitudinal test of self-determination theory’s motivation mediation model in a naturally occurring classroom context. Journal of Educational psychology, 104(4), 1175-1188.

Kusurkar, R. A., Ten Cate, T. J., Vos, C. M. P., Westers, P., & Croiset, G. (2013). How motivation affects academic performance: A structural equation modelling analysis. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 18, 57–69.

Liu, D., Chen, X. P., & Yao, X. (2011). From autonomy to creativity: A multilevel investigation of the mediating role of harmonious passion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 294.

Muraven, M., Gagné, M., & Rosman, H. (2008). Helpful self-control: Autonomy support, vitality, and depletion. Journal of experimental social psychology, 44(3), 573-585.

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. School Field, 7(2), 133-144.

Nix, G. A., Ryan, R. M., Manly, J. B., & Deci, E. L. (1999). Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. Journal of experimental social psychology, 35(3), 266-284.

Núñez, J. L., Fernández, C., León, J., & Grijalvo, F. (2015). The relationship between teacher’s autonomy support and students’ autonomy and vitality. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21, 191–202

Núñez, J. L., & León, J. (2015). Autonomy support in the classroom: A review from self-determination theory. European Psychologist, 20(4), 275.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Wynn, S. R. (2010). The effectiveness and relative importance of choice in the classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 896-911.

Roth, G., Assor, A., Kanat-Maymon, Y., & Kaplan, H. (2007). Autonomous motivation for teaching: how self-determined teaching may lead to self-determined learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 761-774.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000a). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 25(1), 54-67.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000b). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model. Journal of personality and social psychology, 76(3), 482-497.

Su, Y. L., & Reeve, J. (2011). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 159-188.

Copyright © 2018 E.J. Masicampo. All rights reserved.